Ramadan in the Eyes of the Strangers.. How Did World Travelers Describe Egypt's Nights?

SadaNews - Many travelers, both Muslims and foreigners, visited Egypt during Ramadan across different times, all deeply engrossed in describing the habits and traditions of the Egyptians. Among them were Ibn Battuta, Ibn al-Hajj, Ibn Jubair, and Nasir Khusraw.

Among the foreign travelers was Father Felix Fabri who visited Egypt in 1483 and published a book titled "Voyage en Égypte," in which he recorded his first night in the streets of Cairo illuminated by torches and lanterns. It was translated into French by Jacques Mason from the original Latin of Fabri. Similarly, traveler Bernard von Breidenbach wrote about Ramadan nights in Cairo in the mid-fifteenth century.

Ramadan particularly attracted the attention of the scholars of the French campaign, especially the "musaharati" who roams the streets of the protected city at night during Ramadan, beating his drum to wake people for Suhoor.

Professor Dr. Abdel Fattah Ashour, the doyen of Egyptian historians and a professor of medieval times, refers to the origin of the suhoor tradition in Egypt, when the protected city was divided into four quarters, beginning with the "Official Quarter" patrols who would carry drums and roam the houses to awaken the residents, tapping on doors beside the drum.

From the beginning, the people of Alexandria were accustomed to announcing suhoor by knocking on doors and calling the residents by their names.

The History of the Musaharati

Some claim that the first appearance of the "musaharati" in Cairo was during the time of Anbasa ibn Ishaq in the year 228 AH/843 AD, when a man would walk daily from the city of Al-Askar in Fustat to the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As calling people to rise for suhoor.

The Fatimid state paid significant attention to celebrating the arrival of Ramadan and reviving its nights by lighting mosques and streets with bright lights from sunset to dawn throughout the month.

The rulers of the Tulunid state would pray in the Ibn Tulun Mosque and allocated a council in the ruling palace for religious chanting, featuring 12 singers who took turns performing religious songs until dawn, glorifying Allah and reciting the Quran in melodious tones throughout the month.

Mamluk sultans were accustomed to giving gifts during Ramadan to their close associates among the princes and officials, with trays of sweets topped with a "purse of gold." In accordance with the nature of the month, they also honored the general populace. Sultan Al-Zahir Baybars - according to Dr. Saeed Abdel Fattah Ashour - allocated enormous kitchens capable of preparing iftar for thousands of fasting people, numbering five thousand daily.

The sultans freed slaves, and some even freed thirty slaves during Ramadan alone, equal to the number of days in the month.

Some of them ordered the preparation of a royal spread in a golden hall to which princes, officials, elites, and various groups were invited every night, extending about 174 meters long and four meters wide, attended by many residents of Cairo; some would attend more than one night, and the cost amounted to three thousand dinars per night.

Sultan Barquq ordered the slaughter of "25 cows" daily throughout Ramadan, cooking their meat and distributing it along with thousands of loaves of bread to the people in mosques, neighborhoods, and even prisons.

The distribution of meat was not limited to the sultans; the wealthy were accustomed to sharing their meat and alms with the poor, as noted by the French traveler Jean Ballard after his visit to Egypt in 1581.

After Taraweeh prayers, the reciters would recite the Quran, and on the last night, they would recite it completely. When they complete it, the muezzins would chant spiritual supplications, glorifying Allah, and the sultan would shower them with dinars and dirhams.

Some scholars would read Sahih al-Bukhari in the citadel, commencing its reading in the presence of the sultan, judges, and scholars.

The scholars and judges would hold a council in Al-Azhar Mosque chaired by the chief judge from the first nights of Ramadan, and the caliph would send them the finest varieties of food and sweets.

Dr. Ali Hassan, a professor of Mamluk history, notes that the Fatimid sultans participated in taraweeh prayers with the people, and "they brought forth many forms of goodness and charity during this month, which benefited all the subjects."

The Generosity of Egyptians

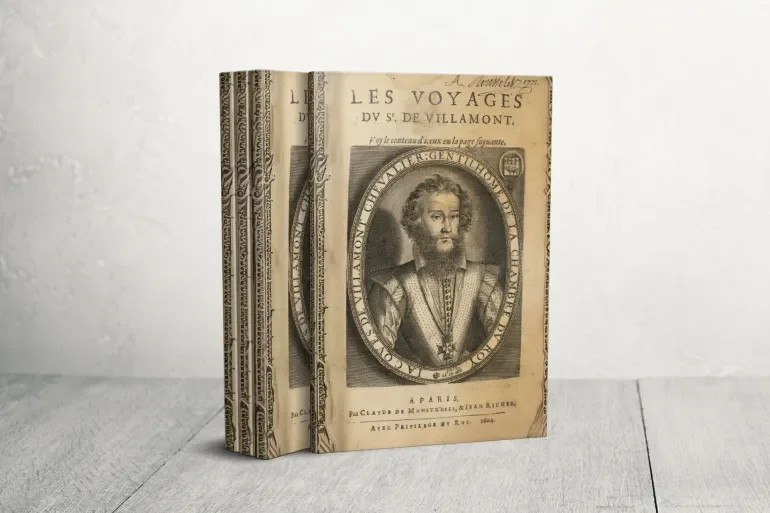

Among the French travelers was the artist Jacques de Villamont (1560-1625) who visited Egypt in 1589 and published a book titled "Les Voyages du seigneur de Villamont" in 1589. He noted that he rented a room overlooking a main street in the protected city to observe the Ramadan celebrations, the processions of Sufi dervishes, describing the circles of remembrance, the illuminated mosques, the bustling markets, and the Iftar gatherings to which friends were invited.

He described the Egyptians as generous, stating: "They have a beautiful custom of sitting on the ground, eating in an open courtyard or in front of their homes, and warmly and sincerely inviting passersby to their food."

The French scholar Guillaume André Viotto, who authored the study "Music and Singing among Modern Egyptians," included the profession of "musaharati" in the famous French campaign book "Description de l'Égypte."

He elaborated on the musaharati: "They are people whose singing is only heard during Ramadan, and they are called musaharati. They chant their poems every day just before dawn, keeping to that timing with strict modesty."

In his study included in the book "Description de l'Égypte," Guillaume André Viotto describes the workings of the musaharati: "The musaharati does not stray from the agreed-upon streets of his area among the musaharati, and he pays a fee to the neighborhood guard for the entire month. He recites religious prayers, some poems, and some tell short folk tales and praises of the heads of households by name, and whoever of the sons, but is prohibited from mentioning the names of women."

There was a third Frenchman who also participated in the French campaign in 1798, Gaspar de Chabrol, who came to Egypt as part of the campaign at the age of 25, and shared with his colleague Viotto the study of Ramadan customs and traditions included in the book "Description de l'Égypte."

He noted: "Every Egyptian strives to accomplish his work quickly during the day as much as possible, to sleep for a few hours. You will see farmers lying under palm trees after finishing their morning work, while merchants stretch out in their shops, and the public sleep on the streets beside the walls of their homes, while the wealthy recline on luxurious couches during the hours before sunset, and all rise before sunset to perform ablution, pray, and break their fast."

Chabrol added: "Mosques remain lit until dawn, and the most virtuous people spend their nights at home engaging in beneficial conversations. Many of the public listen to storytellers of popular tales in cafes, recounting the victories of Abu Zayd al-Hilali or the biography of al-Zahir Baybars in captivating styles."

By the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte, the first volume of the book "Description de l'Égypte," focusing on social studies, was published in 1809 by Gaspar de Chabrol, eight years after the campaign left Egypt.

Staying Up Until Dawn

The fourth scholar of the campaign who was drawn to the customs and traditions was engineer and historian François Jomard, who has a study entitled "Description of the City of Cairo and the Citadel," which was also included in "Description de l'Égypte." He noted that: "Everyone refrains from food, drink, and smoking and any entertainment between sunrise and sunset during Ramadan, but that deprivation is followed by great enjoyment. They go to group prayers with noticeable piety, attend jurisprudence lessons in mosques, some accomplish their work, and others engage in sleep! All celebrate Ramadan nights, where the streets are illuminated, bustling with activity and noise, as they move between markets and cafes until the call to dawn."

A few years after the French campaign, Clot Bey, a French doctor who founded the first medical school in Egypt during Muhammad Ali Pasha's time, published his well-known book "An Overview of Egypt," in which he included his impressions of Egypt and its people, mentioning Ramadan by saying: "Ramadan does not come in a specific season of the year but rotates around it, and its cycle lasts 33 Gregorian years. Contrary to what we believed in Europe that it is a month of entertainment and indulgence, it is a month of deprivation from desires. Fasting does not only exclude eating and drinking throughout the day, but also smoking, snuffing, and fragrant scents. Although Islam permits exemptions for pregnant women, the sick, and travelers not to fast, some pious sick people or travelers do not take the concession! I personally witnessed sick people with fever refusing medicine, preferring death to breaking their fast."

Many people go to mosques, and afterwards some listen to rababa poets and singers in cafes. Others prefer acrobat performances, or circles of remembrance around the tomb of a saint, while some visit the Azbakeya area to hear Turkish music bands, and watch shadow plays and "Arajouz," enjoying cakes, roasted corn, coffee, and fruit juices.

A few decades after the French campaign, the English orientalist Edward William Lane recorded in his famous book "Modern Egyptians, Their Customs and Character" the announcement of the sighting of the Ramadan crescent in ancient Egypt, stating: "Groups would roam the neighborhoods of Cairo, shouting: O followers of the best of God's creation, fast, fast. If they do not see the moon that night, the announcer would cry out: Tomorrow is Sha'ban, no fasting, no fasting."

Lane noted the emergence of 'musaharati' every night as they raised their voices in prophetic praises, including:

Awake, O you who are careless.. unite with the merciful

O sleeper, unite with the everlasting

O careless, worship Allah

O sleeper, worship your Lord

He who created you does not forget you

Arise for your Suhoor

Ramadan has come to visit you.

The musaharati knew the names of all the residents of each house and called each by name: "May Allah make your nights joyful, O so-and-so.." in exchange for two, three, or four piastres from each house during Eid.

A Rich Social Life

In his book "Burton's Journey to Egypt and Hijaz" published in 1853, British traveler Richard Burton recorded important moments: "The cannon for Iftar is fired from the citadel, and immediately the muezzin calls with his beautiful call inviting people to prayer. The second cannon is fired from the Palace of Abbasiyah, and people shout: Iftar.. Iftar, and all the residents of Cairo rejoice."

Burton observed: "The clear impact of this month on the believers is the solemnity that envelops their temperaments. As sunset approaches, Cairo seems to awaken from its slumber, as people peek from windows and mashrabiyas anticipating the moment of the call to prayer! Some become engrossed in their prayers and glorification, while others gather in groups or exchange visits."

Lane also indicates the "silence of the streets and the slackening of life during the day, and right before sunset, an Iftar table is laid out in the reception room, where the head of the household receives his guests. A large silver platter adorned with dishes of nuts, raisins, sweets, and drink containers is prepared for the sudden arrival of guests, and smoking equipment is at the ready."

At the call for sunset, the head of the household, together with his family (or guests), would drink rose or orange syrup, perform the sunset prayer, and then have a snack of nuts and smoke. They would then have a refreshing drink followed by their Iftar, often consisting of meat and delicious foods, then perform the evening prayer, followed by the Taraweeh prayers in congregation in the mosque.

Some musaharati would occasionally recite parts of religious miracle stories such as the Isra and Mi'raj, and would maintain silence if they passed a house grieving the death of a loved one.

Edward Lane recorded that middle-class women would place a coin inside a wrapped paper, light its edge, and throw it from the mashrabiyya to the musaharati to see its location and he would chant some prophetic praises or tales of battles between co-wives.

He spoke of the Night of Decree, when the Quran was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, which is better than a thousand months, and "Muslims believe that the gates of heaven are opened during it, and their supplications are answered."

Source: Al-Jazeera

The Body Under Algorithmic Surveillance: How Technology is Changing Our Relationship with...

Email Newsletters.. A Safe Haven for News Audiences in the Era of Digital Chaos

Massive Recall Hits Nissan: Engine Issues in 2023-2025 Models

Ramadan in the Eyes of the Strangers.. How Did World Travelers Describe Egypt's Nights?

Innovative Tricks for Women during Ramadan.. Here’s How to Organize Time in Ramadan

70 Years Above the Minaret.. Muhammad Ali Al-Sheikh, The Guardian of the Damascus Choir's...

Palestine Flag Raised at Berlin Festival and "Yellow Letters" Snatches the Gold